“Yes, I killed him. I killed him for money–and a woman–and I didn’t get the money and I didn’t get the woman. Pretty, isn’t it?”

Oh, the delicious irony. When I think of film noirs, images of Double Indemnity dance in my head. It was the film that truly defined the noir as I know it today. If The Maltese Falcon was the sketching, then Double Indemnity was the paint, leaving brush strokes of black, white, and a wonderful mix of gray. In just three years since Bogie cynically smirked through the whirlpool of lies, deception, inner-demons (and one phony bird statue) of the reformed Hollywood, Double Indemnity poured in characters even more vile, self-serving and murderous–and as engrossing as any characters in films that have been produced before or since.

Oh, the delicious irony. When I think of film noirs, images of Double Indemnity dance in my head. It was the film that truly defined the noir as I know it today. If The Maltese Falcon was the sketching, then Double Indemnity was the paint, leaving brush strokes of black, white, and a wonderful mix of gray. In just three years since Bogie cynically smirked through the whirlpool of lies, deception, inner-demons (and one phony bird statue) of the reformed Hollywood, Double Indemnity poured in characters even more vile, self-serving and murderous–and as engrossing as any characters in films that have been produced before or since.

Take, for example, femme fatale Phyllis Dietrichson (Barbara Stanwychk) as she drives her car with her husband in the passenger seat and her lover, Walter Neff (Fred MacMurray), hiding in the back. Suddenly, she pulls over and honks the horn. Instantly, Walt strangles her husband to death. We only hear the sounds of a struggle–the camera stays on Phyllis’s face. Her lips curl into a slight smile–as if she relishes the danger almost as much as the freedom and monetary gain from her husband’s demise. Or maybe more so.

The allure of suspense and danger is perfectly expressed through the moments of dark shadows; the stark contrasts within its black-and-white canvas and the moments of suspense injected by director Billy Wilder, who devilishly teases our sensibilities of right-and-wrong. Following the murder, the duo arranges a charade that ends with them dumping the body on railroad tracks in order to give the appearance of an accident. As they are about to peel away, the car refuses to start. Walt tries again and again until, finally, the car springs back to life. The two leads breathe a sigh of relief. At that moment, so do we.

Originally, Wilder filmed the scene of two simply driving away without any hiccups in the plan. Afterwards, Wilder got in his car and couldn’t start the ignition. Then the epiphany hit him. He ran back into the studio and reshot the scene as it plays in the finished film–with the car stalling. MacMurray thought the idea was ludicrous. Why would the car not start immediately? But the gimmick worked so well that it has been duplicated hundreds of times in many films that followed (to the point where it’s become a cliché of horror movies). Yet, even after numerous viewings, my heart always skips a beat. As Walt desperately cranks the engine, I always pray that the damn engine will start.

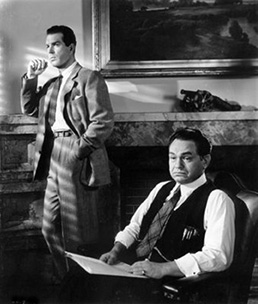

Amongst Indemnity’s many trendsetters is the set-up: it starts at the end. The film opens with Walt lethargically entering his insurance building; his face is draped in shadow or turned away from the camera as he makes his way into the office of his co-worker, Claims Analyst Barton Keyes (Edward G. Robinson). His face is drenched in sweat, his breath is heavy. We see a blood spot on his left shoulder as Walt begins to dictate his story into an audio recording. We flashback and learn how things went so wrong.

As indicated, Walter Neff, a 35-year-old insurance salesman, was looking to score a big sale with a rich business man, Mr. Dietrichson. When Walt makes a house call to renew the man’s current policies, he’s greeted instead by his luminous wife, Phyllis, whose subtle seduction brings Neff down to the darkest corners of his soul. During their first encounter, Phyllis greets him from the top of her staircase balcony, wearing nothing a towel. She’s formal and cordial, with a hint of obvious sultriness. Neff is instantly taken by her spell. As he waits, his voiceover tell us, “I was thinking about that dame upstairs, and the way she had looked at me, and I wanted to see her again, close, without that silly staircase between us.”

Phyllis returns, fully-clothed, and greets Neff in the den, recognizes his immense attraction and sets her trap. Neff begins telling her about the additional policies he provides. When Neff mentions accident insurance, director Billy Wilder once again focuses the camera strictly on Stanwyck. She prances back and forth, listening attentively, thinking hard, never wavering or hinting that he just planted an idea in her head. Neff won’t know what hit him.

The two begin a love affair. Walt toys with the idea of killing Phyllis’s husband so the two can be together and possibility collect a huge sum from his insurance. Later, Neff meets with Phyllis’s husband and tricks him into signing an accident insurance policy that will pay the beneficiary, Phyllis, $50,000 (in 1944 dollars) in the event of his death. Also, if he suffers an accident in an unlikely case scenario–such as on a moving train–the payment is doubled. Neff, a tenured insurance man, knows all of the ins-and-outs, all of the loose-ends needed to patch up in order for the scheme to work. As expected, the murder goes off without a hitch, as does the manipulation to make the death appear like an accident. Of course, everything goes wrong.

For a film that is lean, taut and has a wonderfully constructed narrative, there is one scene that baffles me. As Walt prepares the final phase for his murder, Barton visits his office and offers him a job as his personal assistant (for a few dollars less). Why does he select Walt? Because he likes Walt and trusts him. Walt, not wishing to be pinned to a desk, politely turns it down–even though the job is perfect for him. What is the purpose of the scene? I can only surmise two possible motives: It suggests the mutual respect and friendship between the insurance co-workers. It also indicates how Barton represents Walt’s saving grace from his downward spiral. Barton casually mentions the one woman he almost married long ago—until he had her researched. Too bad Walt didn’t listen.

The two represent a bond that’s missing between Walt and Phyllis: one of mutual respect and affection. Phyllis and Walt even appear more excited by temptation of their murder plot than each other.

Like its precursor, M, Double Indemnity tells the story of bad people who do a terrible thing and spend most of the film trying to cover their tracks and elude capture or something much worse. Yet, somewhere during the course, we get bamboozled–we can’t help but get involved in their plot–tensing up whenever it looks like Walt and Phyllis will be caught. Wilder manipulates the audience akin to his peer, Hitchcock, but Wilder is more reserved with his direction of suspense, relying more heavily on the performers’ body language and faces.

There’s the scene Walt gets a phone call in his apartment from Phyllis, who is five minutes away and wants to come see him. The moment Walt hangs up, he receives a knock on his door. It’s Barton! At this point, Barton is researching Phyllis’s claim for her husband’s death, but knows nothing of Walt’s connections or scheme.

Walt entertains his unexpected visitor, knowing that Phyllis’s mere appearance will incriminate him instantly. He plays cool, even as Barton voices his theory that he thinks Dietrichson’s death was neither an accident nor suicide. What else could it be?!

While Walt labors over this development, his mind races, his eyes constantly wander back to the doorway. He projects his voice loudly so Phyllis might hopefully overhear his conversation before she enters. But McMurray plays it just right, maintaining a casual and calm exterior as his mind struggles to tame the escalating nervousness from the dual threat of Barton’s curiosities and Phyllis’s eminent arrival. McMurray exerts the perfect level of stiffness and quick glances to suggest his worry. Wilder wisely doesn’t cut back to Phyllis–we don’t know when she’ll turn up–until she’s right outside his door and hears the voices of two men.

Soon, Barton takes his leave. Walt sees him out, suspecting Phyllis will pop out of the elevator. Instead, he feels like a slight nudge on the door–Phyllis is hiding behind it. Of course, doorways to apartment (or homes) do not open outwards, but this is one rule that’s compromised for the sake of the suspense. Of course, Barton teases us further by creeping close to the door. And like in Fritz Lang’s M, we catch ourselves holding our breath for the bad guys.

Between Maltese and Indemnity, we have two of the most famous femme fatales of the silver screen. After rewatching both, I pondered if men, in general, have more of an affinity towards these films than women. Are these female portrayals liberating or simply demeaning? One could presume that the noir suggests that women’s freedoms spell doom for the male species. Or do they actually imbue sympathy for women? Are the femme fatales committing these actions to escape the confinement of the male-dominated world?

I always lean towards the last option. The noir seems to present strong-willed females who defeat, or at the very least, attempt to defy the restrictions of the establishment. They fend off and, in many cases, destroy the domineering men through the limited tools they possess: usually including their power to seduce. In most noirs, the chief male protagonist is either a lone cynical detective whose keen senses are averted by their sexual desires. Or their thieving, murderous schemes are undermined by a woman, who weaves a thicker layer of manipulation. The women of these films are most dangerous. They have an agenda they’ve orchestrated on their own, which usually leads to some form of monetary gain or liberation. They frankly don’t care much for starting a romance, but use the conventional wisdom–the idea that every woman longs for a man, for a love–in order to deceive and undo males who buy into the idea.

In this case, Barbara Stanwyck’s Phyllis Dietrichson demonstrates her power and authority through her charm and subtle sexuality. The fault is on Neff for being the sap taken in by the flirtations of a lonely, self-serving woman, but what is Phyllis’s overall scheme? She clearly doesn’t love Walter, but what does she plan to do after the dust settles?

The ultimate fates of Barton, Walt and Phyllis end with an exchange of gunshots–each bullet ringing equally loud and brutal. Like The Maltese Falcon, most of its influences are commonplace in Hollywood. But few have duplicated the icy, biting dialog, the dimensions of three leads, the ominous shadows that haunt them, and, of course, Wilder’s taut direction that asks us to question our very natures. And like Walt, first time viewers may fall prey to the seduction of Phyllis. Edward G. Robinson was a leading man until Wilder convinced him to take a supporting part. He chews every ounce of his role. His final moments with Neff are touching. They exchange one last cigarette and a tender moment of affection that would lead to another avenue of interpretation that I’ll spare for another time. Instead, we have two men who inhabit the true love story of the film. No matter how you interpret the portrayals of women in these movies, there’s always an element of lost love buried within the cracks. Pretty, isn’t it?